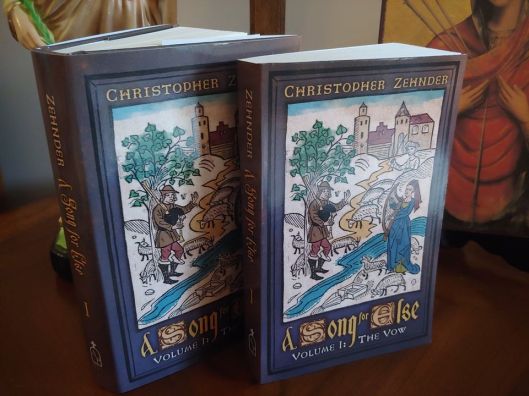

By Christopher Zehnder

What follows is the Foreword (or “what gentlemen call a Preface,” in the words of Hilaire Belloc) to my trilogy of novels, A Song for Else, set in the opening years of the Reformation in Germany, explaining some of the influences that inspired me to write the work. The first two of the volumes (The Vow and The Overthrow) are available from Arouca Press. The third will hopefully soon be available.

This novel, A Song for Else, has in a sense been some 38 years in the making. The first germs of it were planted in my mind when I was 19 years old, soon after my conversion to the Catholic Church. Coming from a family that has been Lutheran since Martin Luther and had, moreover, helped found the Missouri Synod Lutheran Church, I had as a child and a young adult a keen sense of the religious heritage in which I first learned the name of Christ. One does not inherit such a tradition without it deeply affecting him. Indeed, the Jesuit priest who brought me into the Church said of me in those far-off days, “You can take the boy out of the Missouri Synod, but you cannot take the Missouri Synod out of the boy.” Looking back on those days, I think he was right.

I trust that I am far less culturally Lutheran than I was 38 years ago; yet, as Dorothy Day once said (and I paraphrase), “the bottle never stops smelling of the liquor it held.” Perhaps it was to understand myself, what made me who I am, that the thought never left me of writing a novel – in this case, a trilogy – set in the period of the German Reformation. There is much that is personal in it. The action of the plot centers around the storied city of Nürnberg, from whose environs my family came. The name of the main character, Lorenz List, has personal references. I was born on the feast of St. Lawrence (Lorenz) the Martyr, and List is taken from my great–great–grandfather, Johann List, who came from Mittel–Franken in Bavaria to America in 1845.

This novel, however, is not an exercise in self-awareness therapy. It is not about the author. It tells the story of Lorenz List, an intellectual and sensitive young man who, through fortuitous circumstances, finds himself cast into a society very unlike the peasant culture in which he was born and raised. It is a story of love, both love for God and love of a woman, and how these loves influenced and shaped the protagonist. It is a story of a society, fundamentally Christian and Catholic, but shot through with religious and philosophical confusion and seething with revolutionary feeling. It is a tale of a young man coming of age in a time where old certainties are probed and questioned, faith is challenged, and men’s minds are troubled by apocalyptic foreboding. It is, in short, a story of an age not entirely unlike our own, for in it the seeds of our time were planted.

When I was younger, perhaps purer, but certainly more impressionable, I read Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. What I read deeply stirred me, particularly Thoreau’s reasons for retreating to the woods. “I went to the woods,” he wrote, “because I wanted to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” Thoreau said he “wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.” Though I could not fully articulate what it meant to “reduce life to its lowest terms,” I knew it was something I wanted to do. I wanted my small house on Walden Pond. I longed to hoe my patch of beans.

When I was younger, perhaps purer, but certainly more impressionable, I read Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. What I read deeply stirred me, particularly Thoreau’s reasons for retreating to the woods. “I went to the woods,” he wrote, “because I wanted to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” Thoreau said he “wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.” Though I could not fully articulate what it meant to “reduce life to its lowest terms,” I knew it was something I wanted to do. I wanted my small house on Walden Pond. I longed to hoe my patch of beans.